Learning to Look

Heather, Dupont Circle, Washington DC, December 2012

Heather, Dupont Circle, Washington DC, December 2012

I knew nothing worth knowing about art when I met her, nor was I particularly motivated to learn. Art museums bored me; when I went to one, I rarely remembered any individual work – I remembered the visit. I’d been to Florence and passed on the opportunity to see the Uffizi because the process of getting tickets involved massing a counter (Italians never seemed to get in line for everything, an attitude I respected but didn’t leave me with a desire to participate in the scrum if I didn’t have to).

I wasn’t interested in art. I was interested in her, with that glittering enthusiasm that fresh love brings.

So at first I wasn’t looking at art. I was looking at her looking at art.

It wouldn’t be the first time I’d picked up something worth knowing from someone I’d fallen for. I came to college with the palate of a preschooler; chicken nuggets and mac and cheese were visible slices on the pie chart of my nutritional intake. I only started eating more sophisticated food because all the people I went on dates with seemed to want to go to hole-in-the wall ethnic restaurants. A first date with a dashing do-gooder was a benefit dinner to (I kid you not) buy Thai women out of sex trafficking.

I went down the line of steam tables thinking, “Don’t know what that is, don’t know what that is, don’t know what that is, POTATOES.” I scooped the potatoes, in a fragrant yellow sauce, onto a heap of rice on my plate. Back at the table, I listened to my date talk about climate justice, and stuck a fork in one of the potatoes and put it in my mouth, only to find that when I bit down on it…my teeth bounced right off. I was eating my first sea scallop, but at the time, I thought, “I have no idea what is in my mouth but I like this guy and I don’t want to spit it out in front of him.” I ate it. Our budding romance did not survive, but my interest in Thai food did.

Watching her, I quickly realized that I’d been approaching museums like the worst kind of blockhead. Why had I never thought, “You know, taking the number of works in the museum and dividing by the number of minutes I’m going to be here is probably not the best way to experience this.” She rushed by many pieces, even giving some a dismissive hand gesture that seemed totally out of character. Now I was learning something: she would not give that hand gesture even to the most obnoxious bro on the bus for mansitting across three seats, texting obliviously, while an older man and a woman holding a baby looked on, but here, she would take up the sceptre and decide who got to stand in her presence and who wasn’t worth her time.

It was a revelation, but still, one about her, not about art.

It might never have been about the art if I hadn’t been sick that day. We were in DC, indulging ourselves with the amazing free museums. I was still recovering from a serious illness , and going from our hotel in Dupont Circle to the museum district was the longest walk I’d taken in quite awhile, and suddenly I could feel the insult to my body that the surgery had been. Usually, I slowed my walking pace to meet hers; now, it was an effort for me to keep up with her, even though I knew she was not going very fast.

Inside the museum, she sped up, dismissing ranks of courtiers lining the walls until she found one that was worthy of her attention. Fortunately for me, there was a wide bench with a leather padded top in front of it.

I sat. I watched her watching the work. And I watched her walk off, regal, crisp, focused, making no move to take her long wool coat off. I, on the other hand, was dying, overheated from the exertion but torn between the effort of standing to follow her and the effort of taking my jacket off.

I wanted to get up, but it just seemed like a bad idea. So there I sat, a trickle of sweat running down from my hairline into my collar.

I took off the wool tweed hat she’d given me as a gift, and pulled off my gloves, putting them in the hat beside me on the bench. I was alone in the gallery; well, there were no other humans there. But I had already made the surprising discovery that being alone in a room with a work of real mastery was not the same as being alone in a room. Great art has a palpable presence; you can feel it in the room with you. Here I had eight companions, all of them strangers to me. Some later became friends, a Kehinde Wiley canvas and a Louise Bourgeois sculpture.

I unbuttoned my coat and took it off awkwardly, favoring my left side. As I twisted to my right, something gold caught my eye. I extricated myself from my coat, my shirt still stuck to my back, and turned to face it.

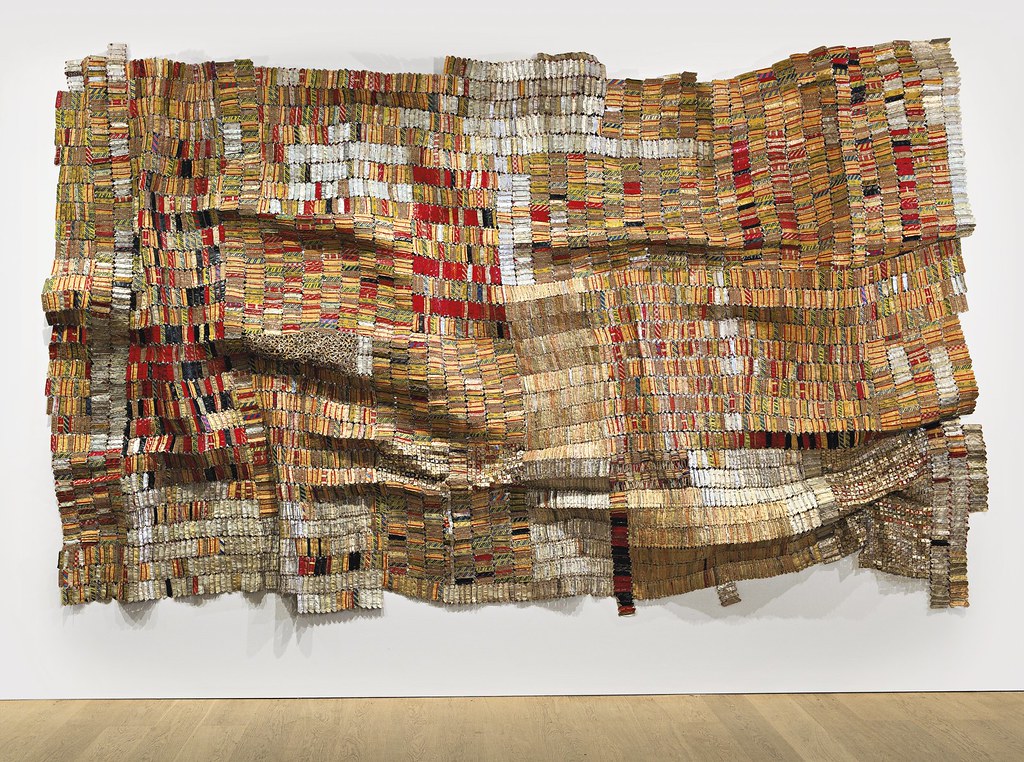

A huge piece, at least ten feet high, fourteen feet wide. Not a painting, but also not a sculpture. A hanging? A weaving? But made of metal.

Man’s cloth II, El Antasui, sculpture/weaving, aluminum and wire

I sat. It may have been the first time I’d ever spent more than ten minutes with an artwork. Something started to happen, first to me and then to the work. My physical discomfort started to disappear, and I had the eerie feeling that it wasn’t just that I was sitting still. There was something salutary happening when I finally stopped and engaged with a work, something that gave me a feeling of well-being that was palpably physical.

Then, something started to happen to the work. It was the first time I realized that works of art were like very slow movies; that if you were patient enough, they would change, move. The work had more than one thing to say to me; it was deeper than just the sound byte I’d previously given it time for. Time thinned out, disappeared, flowed out the door.

I don’t know how long it had been since she’d left the room where I sat on the bench. When she returned, she did not approach, but stood framed by the massive doorway, her facial expression an inquiring one. I gestured at the work on the wall. She nodded. She understood.

She took her place beside me on the bench, and together, we looked.

My partner, Rhode Island artist Heather Adels, died in March 2017 of a sudden cardiac arrest at the age of 41. More about her life and work here.